Master Guide to German Articles: The Secrets of Das, Die & Der

If you are an English speaker, chances are you will feel quite confident once you start learning German. After all, they’re both Germanic languages, right? That’s why so many German phrases sound so familiar to us. Take Gute Nacht (Goodnight), for example, or Ich habe zwei Brüder (I have two brothers). It seems German is easier than you might have expected.

But then you meet them (sinister music playing in the background), and by them, we mean German ARTICLES, and life does not look so bright anymore.

What Are Articles?

Before we explain why German articles are so unpopular among language learners, let us refresh your memory and remind you what an article is.

In English, it couldn’t be easier to explain. An article is any of the English words “a”, “an”, and “the”, which we use before nouns. If you know exactly what you’re talking about (or if there’s only one of its kind), you use “the”. If you don’t know who or what you’re talking about or you mention something for the first time, you use “a” or “an”.

The problem is that, in other languages, the words that fulfill this function are much bigger in number and much trickier to use. How tricky? Well, let’s compare a few sentences in English and German.

The chair with the yellow elephants on it.

The apartment that we saw this morning.

The book that you told me about the other day.

As you can see, English uses the same definite article, “the”, to refer to chairs, books, and apartments. In German, however, nouns (both palpable, like “book”, and abstract, like “love”) are gendered, and they take different articles depending on whether they are feminine, masculine, or neutral.

Gender can be natural or biological, i.e, (man, woman, brother, sister, etc.) or grammatical, which means that the thing in question is not naturally gendered but a grammatical gender category has been assigned to it anyway.

The words in the examples above, for example, all have different grammatical genders and, as a result, they take different articles. And in case you’re wondering, yes, these grammatical categories are as random as they seem. In German, “chair” is masculine, “apartment” is feminine, and “book” is neuter. Thus:

Der Stuhl mit den gelben Elefanten darauf.

Die Wohnung, die wir heute Morgen gesehen haben.

Das Buch, von dem du mir neulich erzäht hast.

German Articles Are Inflected by Case

To make things worse (sorry!), German articles also change according to the grammatical case. “What the heck is a case?”, you might be thinking at this point, with your arms crossed and an indignant frown.

Grammatical cases tell us what role a word fulfills in a sentence, i.e, what the relationship is between that word and other words in the same utterance. Most languages have four basic grammatical cases: nominative or subjective, accusative or objective, dative (when the word is the indirect object), and genitive or possessive.

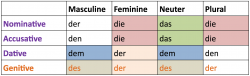

Different combinations of gender and case, then, will require different definite articles.

The good news is that not all possible combinations require different forms. For instance, feminine and plural nouns in the nominative or accusative case are the same, and so are masculine and neuter nouns in the dative or genitive cases.

Can I Make This Simpler?

If you still find it all a bit overwhelming, there is something else you can do to make things easier. And that is dropping the genitive case. Yes, we mean it. Forget about it entirely. Well, not entirely. But, if you’re a beginner and you’re experiencing frustration, then it won’t hurt you to omit one little case for now.

After all, languages are means for communication and as long as you can make yourself understood, that should be enough if you’re just starting your learning process.

Why the genitive case, and not any other? Well, because very soon it might disappear altogether.

Due to a natural tendency on the part of speakers to simplify their language, native German speakers seem to be using the dative instead of the genitive case more often every year. According to linguists, this process is happening so fast that the genitive case might be pushing the daisies any day now.

Gender in German: A Few Quick Tips

Okay, now that we’ve decided to ignore the genitive case and that we know what the different combinations of gender and case are, life should be easier, right?

Well, yes and no. Because there is a question that remains unanswered. How will you know if a noun is masculine, feminine, or neuter? For nouns whose natural gender is easily identified, this won’t be a problem. Let’s take a look at a few examples:

Der Mann (the man), der Bruder (the brother), der Vater (the father), der Sohn (the son), der Ehemann (the husband).

Die Frau (the woman), die Schwester (the sister), die Mutter (the mother), die Tochter (the daughter), die Frau (the wife)

Other word types, such as jobs and professions, have both masculine and feminine declensions. The feminine form is most often derived from the masculine by the addition of final “-in”. Take a look:

The doctor: Der Dotkor / Die Dotkorin

The Singer: Der Sänger / Die Sängerin

The teacher: Der Lehrer / Die Lehrerin

What About the Other Nouns?

Unfortunately, not all nouns in German have a natural gender. In fact, most of them don’t.

Wait, don’t give us that look again, we swear you won’t have to memorize the genders of ALL German nouns by heart. As usual, there are tricks you can learn to make it easier for yourself.

Gender-related doubts, for example, can usually be solved by looking at the noun endings or suffixes. All you have to do is learn which endings belong to each gender and you’re ready to go.

For example, nouns with endings -ant/-ent are usually masculine (Emigrant, emigrant); nouns with -e are usually feminine (Nase, nose); and nouns with -chen are normally neuter (Häschen, bunny).

How Meaning Can Help You With Gender

And then there is another shortcut that might help you to figure out the gender of nouns. Although we said that grammatical gender is often arbitrary, there are certain categories of meaning in which words tend to have all the same gender.

For example, words related to time, such as months or days of the week are normally masculine: Januar (January), Samstag (Saturday)

Weather-related vocabulary, like Wind (wind) and Regen (rain), are usually masculine too.

Names of ships, on the other hand, are feminine words. Titanic, for example, is feminine as Rose, and not masculine as Jack. (This shouldn’t be too hard for English speakers, as we often refer to ships with feminine pronouns).

Motorcycle brands, like Honda, and names of cigarettes, such as Camel, are feminine too.

Last, names of colours are neuter: Blau (blue), Rosa (pink), regardless of the associations that we can make between the colours and gender identity. Nouns derived from verbs also belong to this category: Essen (eating), Reisen (travelling).

Summing up, these are the steps you need to follow to prevent gender from spoiling your fun while learning German articles.

- First, ignore the genitive case for now. Yes, we were not joking.

- Second, study the declensions of German articles for the other three cases.

- Then, try to memorize the most common endings that indicate gender. This will make it much easier to figure out the gender of most German nouns!

- Finally, check the different categories of meaning that tend to indicate gender.

Oh, one more thing. Whenever you learn a new vocabulary item, make the most of your time and learn the German articles that you can use with it. That way, every time you incorporate a new term into your repertoire, you will be revising and fixing grammatical rules as well.

How Can You Put All This Knowledge Into Practice?

Take an online course with us and keep on learning through real conversation with native speakers. Although learning grammar on your own will surely help you, in the end, we all want to use our language skills to communicate with other people, right?

At Language Trainers, we work with the most passionate German teachers from all over the world who are genuinely eager to share their language and cultural insights with their students. Send us a message on our website and we will contact you in no time so you can start working on your fluency!